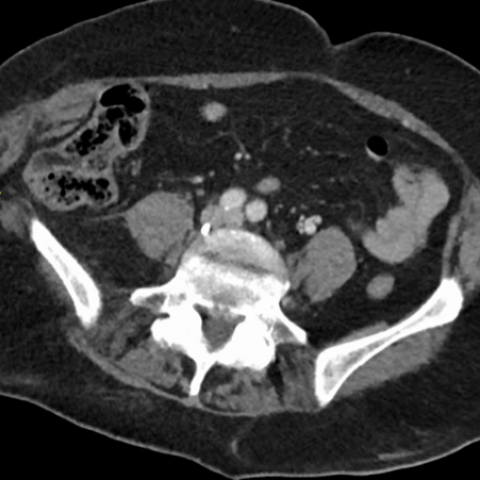

Axial CT abdomen and pelvis portal venous phase

Abdominal imaging

Case TypeClinical Cases

Authors

O’Neill M1, McQuade C2, Torreggiani W2

Patient69 years, female

We present the case of a 69-year-old female who sustained significant blunt thoracic and abdominal wall trauma in a farmyard accident. The patient was haemodynamically stable on arrival into the emergency department, but complained of right sided abdominal pain. Secondary survey demonstrated a tender swelling in the right flank.

The patient underwent a routine trauma CT series of the thorax, abdomen & pelvis. In our institution, this constitutes arterial phase imaging of the thorax and upper abdomen, followed by portal venous phase imaging of the abdomen and pelvis. No oral contrast was administered.

Review of images of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated an acute fat-containing right inferior lumbar hernia, with rupture of external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis muscles. The lateral wall of the ascending colon traversed the neck of the hernia, without overt evidence of herniation. There was no evidence of bowel obstruction or bowel wall injury.

Expansion of the right lateral abdominal wall musculature with subcutaneous haematoma within the right lateral abdominal wall was also evident.

Thoracic injuries included fractures of the left 7th – 12th ribs, without evidence of pneumothorax or haemothorax. Multilevel lumbar vertebral transverse process fractures were also identified.

Lumbar hernias are rare defects, representing 1-2% of abdominal hernias. [1] They arise in the posterolateral abdominal wall through weaknesses in lumbar musculature or posterior fascia.

Lumbar hernias are classified based on anatomical location. [1]

Lumbar hernias may be congenital or acquired.

Herniation of both intraperitoneal and retroperitoneal structures has been described. [6] Complications are common to other abdominal wall hernias, including incarceration, obstruction, strangulation [8] or nerve injury (collateral branch of subcostal nerve, iliohypogastric nerve). [9]

Lumbar hernias present a diagnostic challenge, due to their relative rarity. Examination may reveal a reducible swelling with cough impulse. A painful, irreducible hernia should raise concern for strangulation. In the setting of trauma, clinicians should consider potential for significant co-existing injury such as pelvic or spinal fractures; or seatbelt-related injuries including major vascular injury, mesenteric disruption or intestinal perforation. [6, 7, 10] In non-traumatic hernias, associated congenital anomalies should be considered.

CT is the gold standard in confirming the presence of a lumbar hernia. Additionally, CT can delineate hernia anatomy and contents, identify potential hernia-related complications, or demonstrate co-existing injuries. [1, 3]

Surgical repair is usually advocated. Open, laparoscopic (transabdominal or retroperitoneal) and minimally invasive approaches have all been described. [1, 9, 11] There lacks consensus regarding operative timing and technique, due to the relative rarity of the condition with paucity of evidence in the published literature to date. [12, 13]

Interpreting radiologists should be familiar with the relevant anatomy of a lumbar hernia, and communicate this information to surgical colleagues to inform operative planning. An understanding of the potential associations of lumbar hernias is also important, such that these may be identified when reporting.

[1] Moreno-Egea A, Baena EG, Calle MC, et al. (2007) Controversies in the current management of lumbar hernias. Arch Surg. Jan;142(1):82-8. (PMID: 17224505)

[2] Grynfeltt J. (1866) Montpellier Med. Quelque mots sure la hernia lombaire. 16:329

[3] Aguirre DA, Casola G, Sirlin C. (2004) Abdominal Wall Hernias: MDCT Findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 183: 681-690. (PMID: 15333356)

[4] Petit L. (1783) Trait des maladies chirurgicales, vol .2. Masson, Paris.

[5] Sharma A, Pandey A, Rawat J et al. (2012) Congenital lumbar hernia: 20 years’ single centre experience. J Paediatr. Child Health. 48(11); 1001-3. (PMID: 23039934)

[6] Suh Y, Ghandi J, Zaidi S et al. (2017) Lumbar hernia: a commonly misevaluated condition of the bilateral costoiliac spaces. Translational Research in Anatomy.

[7] Burt BM, Afifi HY, Wantz GE, Barie PS. (2004) Traumatic lumbar hernia: report of cases and comprehensive review of the literature. J Trauma. 57(6):1361-70. (PMID: 15625480)

[8] Pang RR, Makowski AL. (2019) Inferior lumbar triangle hernia with incarceration. Am J Emerg. Med. 37(6):1218.e5-1218.e6. (PMID: 31027934)

[9] Nakahara Y, Wakasugi M, Nagaoka S, Oshima S. (2020) Single incision retroperitoneal laparoscopic repair of superior lumbar hernia using self-fixating ProGrip mesh: A case report. International Journal of Surgical Case Reports. 67: 120–122. (PMID: 32062114)

[10] Masudi T, McMahon HC, Scott JL, Lockey AS. (2017) Seat belt-related injuries: A surgical perspective. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 10(2): 70–73. (PMID: 28367011)

[11] Clothier JS, Ward MA, Ebrahim A, Leeds SG. (2019) Minimally invasive repair of a lumbar hernia utilizing the subcutaneous space only. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 32(4): 550–551. (PMID: 31656415)

[12] Karhof S, Boot R, Simmermacher RKJ et al. (2019) Timing of repair and mesh use in traumatic abdominal wall defects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Journal of Emergency Surgery. Dec; 14:59. (PMID: 31867051)

[13] Hafner CD, Wylie JH, Brush BE. (1963) Petit’s Lumbar Hernia: Repair with Marlex Mesh. Arch Surg. 86(2):180-186. (PMID: 13951839)

| URL: | https://eurorad.org/case/17261 |

| DOI: | 10.35100/eurorad/case.17261 |

| ISSN: | 1563-4086 |

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.